“Fabbrico, centro di pigiatura”

testo in catalogo di Paolo Barbaro

“Aprono le finestre, ancora per poco”

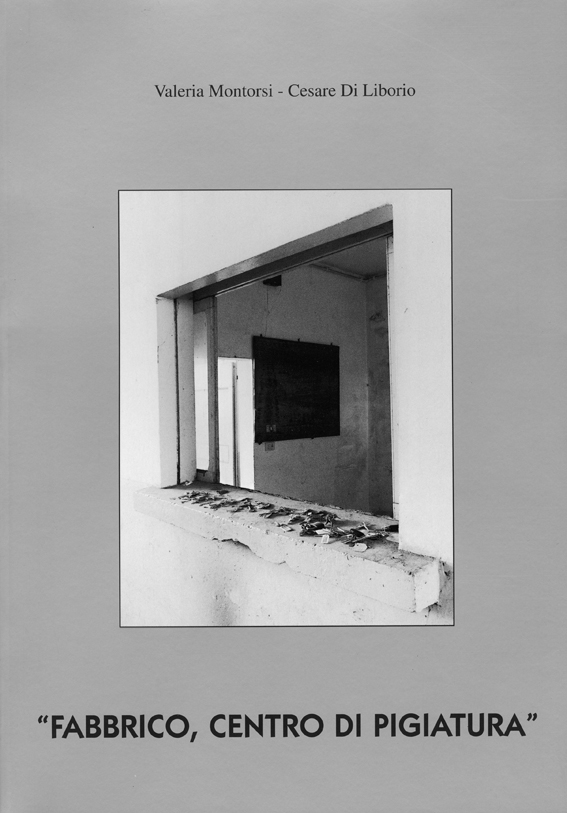

Forse non è la prima volta che qualcuno fotografa gli spazi della Cantina Sociale di Fabbrico, molto facilmente questa è l’ultima volta. Le circostanze sono semplici e lineari. L’Istituto Autonomo Case Popolari di Reggio Emilia e la Cooperativa Muratori Reggiolo progettano un insediamento che comporta la distruzione di questo edificio industriale, decidono quindi di salvarne la memoria con la fotografia; l’incarico è affidato a Cesare Di Liborio e Valeria Montorsi senza alcuna riserva, senza alcuna indicazione. In qualche modo questa operazione è il “negativo” della classica fotografia industriale, di quella che potrebbe essere stata fatta all’edificio al momento della costruzione, quella che forse verrà fatta alle abitazioni che ne prenderanno il posto. Nella classica campagna industriale, pubblicitaria (penso alla tradizione dei Villani a Bologna, di Vasari a Roma) si tratta di costruire l’immagine di un luogo per collocarlo nella memoria collettiva attraverso alcune retoriche ben definite: l’ampiezza dei locali, l’ordine, la pulizia, l’efficienza e la vivibilità che passano anche attraverso una certa efficienza della scrittura fotografica: i colori netti, la definizione alta del grande formato di ripresa oppure la scena gradevole e pacificata. Tutto deve essere ben visibile, illuminato senza contrasti troppo netti, si deve raccontare che non c’è nulla da nascondere.

Qui, invece, abbiamo uno spazio che appartiene alla memoria del luogo, degli abitanti di Fabbrico, magari solo come scatolone vuoto, come volume via via più degradato; ma è uno spazio che sta per uscire dal paesaggio: occorre salvarne una memoria già stratificata, darle una proiezione diversa, una durata diversa.

Non è certo un caso che nei paraggi di questo lavoro troviamo altri fotografi di un certo tipo: Vasco Ascolini è coinvolto nella concezione della campagna di documentazione (Ascolini lontanissimo da ogni ipotesi di fotografia documentaria “trasparente”, sempre fieramente legato ad una scrittura molto individuata, per alcuni metafisica e comunque dichiaratamente soggettiva, proprio nell’alveo della Subjective Fotografie di Steinert degli anni Cinquanta) mentre Nino Migliori si interessa agli esiti, segue lo svolgersi della storia man mano che escono le prime stampe (Migliori per cui i muri, le superfici della città e dei luoghi abitati sono schermo di proiezione della memoria collettiva, scena della scrittura automatica di una civiltà tradotta dalla fotografia che è comunque sperimentazione, del futuro imprevedibile o della memoria altrettanto imprevedibile).

A questo punto altre opzioni, altri modelli, sarebbero stati facili da percorrere. Magari si potevano replicare le descrizioni “cartesiane” della fotografia di architettura, ripercorrere i modi della fotografia di documentazione industriale lasciando al vuoto il racconto della nostalgia, dell’assenza, riprendendo magari la linea inaugurata da Evans negli anni Trenta nelle campagne sugli edifici vittoriani del sud degli Stati Uniti, linea che arriva ad autori contemporanei come Basilico, Guidi, Rosselli e tanti altri.

Oppure si poteva svolgere uno scavo nelle tracce, nei dettagli e negli oggetti abbandonati e trovati come fuori dal tempo storico: i muri delle officine e le grotte di Lascaux, come titolava Brassai un articolo del 1932.

Montorsi e Di Liborio hanno presente tutto questo, ma poi fanno un’altra cosa ancora. Entrano nella cantina, aprono le finestre nel buio, vedono e fotografano subito, si appropriano di uno spazio dopo l’altro con un gesto di esplorazione. Colgono l’orientamento delle luci, programmano i ritorni per avere il giusto orientamento del sole. Lavorano con due formati diversi (24×36 e 6×6) invertendone però la logica: il piccolo formato per gli spazi ampi, per i luoghi dove si è vissuto, il formato medio per le tracce, per i segni dove la materia racconta se stessa. Sanno quindi che la fotografia non è rilievo, impronta della realtà, ma scrittura con una sua precisa sintassi per cui il 24×36 è il bianco e nero del documentarismo, del réportage, il 6×6 è la scrittura del dettaglio, della materia che balza fuori dall’evento e lo mette tra parentesi. Il lavoro a quattro mani è fatto soprattutto dagli sguardi: guardano insieme, si indicano l’un l’altro le cose e ognuno ne scrive una versione. Valeria Montorsi procede per campi e controcampi, la leggibilità delle superfici è a tratti cancellata dalle luci dall’esterno che sfondano, la grana e la polvere stendono velature ruvide sugli stacchi netti di tono. A tratti l’architettura viene presentata con assonanze navali (ringhiere, oblò, paratie e passerelle) e a tratti gli spazi sembrano abbandonati da poco, e a volte i detriti e le macchie di umidità si mangiano l’inquadratura che mantiene comunque un impianto centrale molto solido, la fuga prospettica centrale come l’ombra o la luce proiettate sottolineano sempre la monocularità della prospettiva in fotografia. Riconosciamo i luoghi e lo stesso sguardo frontale nelle immagini di Di Liborio, ma i grigi si arricchiscono, stringono sui segni, sulle forme individuate in modo apparentemente catalogico, in realtà molto proiettivo: siamo vicini alle serie, dello stesso autore, sull’immaginario turistico (Turista per gioco, 1993, che, mi pare, devono qualcosa ad Atlante di Ghirri) e sul viaggio dentro la propria abitazione (Via Parma 14, del 1998) anche se ci si allontana, per forza di cose, dalle iconografie Pop degli oggetti d’uso casalingo a favore di tempi più dilatati, tracce di Morandi, di Klein, fioriture di umidità. E’ come se avvicinandosi alle superfici, al guscio di questo posto che sta per sparire, si producesse un rallentamento dei tempi di lettura, un addolcimento dei toni, uno sguardo che diventa una carezza.

PAOLO BARBARO

Marzo 1999

“The windows are oper, but not for long”

Perhaps this is not the first time the Fabbrico Cantina Sociale Cooperative Winery has been photographed, but this is quite likely going to be the last. The circumstances are simple and linear. The Reggio Emilia Council Housing Authority and the Reggiolo Construction Cooperative are planning a housing estate in the area, which will mean demolishing the old industrial building, and, if it cannot be saved, at least its memory will be preserved through photographs. The task has been given to Cesare Di Liborio and Valeria Montorsi without any reservation, but also without any instruction. Somehow, this operation is like the “negative” of classic industrial photography, of the pictures on the building that could have been taken while construction was under way, or of those that will document the new residential units that will rise in its place. In a typical advertising campaign (I am thinking on the style of the Villanis in Bologna, or Vasari in Rome), the trick is to put together the image on a place in order to implant it into our collective memory through a very well defined use on rhetorical devices. The wide rooms, the organisation, cleanliness, efficiency and comfort must translate into a corresponding efficiency in the photographic language – bold colours, the high definition of the large format, or, otherwise, a pleasant and pacifying scene.

Everything must be clearly visible, the lighting without sharp contrasts, for the underlying effect in the tale told must be that there is nothing to hide.

Here, instead, we have a space that belongs to the memory of the place, of the inhabitants of Fabbrico, perhaps only as an empty shell, as a progressively more degraded volume. Even as a feature of the landscape, the building is destined to disappear, and its memory, no matter how stratified, must be salvaged and given a different projection, a different life span.

It is definitely not by chance that in the periphery of this job there are other photographers of a certain kind: Vasco Ascolini is involved in the conception of the documentary campaign (Ascolini is far removed from any hypothesis of “transparent” documentary photography, and always fier-cely attached to a very individual style that some define as metaphysical and, in any case, avowe-dly subjective, in the wake of Steiner’s Subjective Fotografie of the 50s). Nino Migliori is more interested in the outcome, he follows the progress of the story as the first photos are printed (for him, the walls, the surfaces and textures of a city, town or any inhabited area are a screen onto which to project the collective memory of its inhabitants, a backdrop for the automatic writing of a civilisation translated by photography which is however experimentation of an unpredictable future or a memory just as unpredictable).

At this point, other options, other models, would have been just as easily practicable. Maybe, one could have pursued the Cartesian descriptions of architectural photography, re-tracing the modes industriai documentary photography and committing nostalgia and absence to a void, reviving perhaps the trend inaugurated by Evans in the 30s in his campaigns on Victorian buildings in the South of the United States, a trend that still several followers among contemporary authors like Basilico, Guidi, Rosselli, and many more.

Or else, one might have delved into the traces, details and objects abandoned in a timelessness that robs them of their historicity: the workshop walls as the Lascaux caves, as the title of a 1932 article by Brassai read.

Montorsi and Di Liborio are well aware of all that, but then take an entirely different course.

They step into the premises of the winery, open the windows in the dark, see and take photos at once.

They claim the building room by room as their own. They prowl, they explore. They study the slanting light, pian their visits to catch the sun in the right orientation. They work with two different formats (24×36 and 6×6), inverting their logic – they use the smaller format for the ampler spaces, for the areas where people lived, and the larger format to record the traces, the signs of the matter telling its own story. They know that photography is not a survey, nor is it an imprint of reality, but a form of writing with a very precise syntax according to which the 24x36format is the black and white of documentarism, of reportage, while the 6×6 is the recording of details, of matter leaping out of the event to highlight it. More than a four-hand job, this is a four-eye achievement: they look at their subject matter together, pointing things out to each other, and each writes its own version of what they see. Valeria Montorsi proceeds by shots and reverse shots, the legibility of the surfaces is at times erased by the externallight crushing in, the texture and dust spread a gritty fog on the sharp tone contrasts. Here and there, architecture is presented with naval overtones – rai- lings, portholes, bulkheads, and gangways. Elsewhere, the rooms appear freshly vacated, and the rubble and spots of dampness take over, drowning the shot, which however always maintains a

very solid central focus, with the central retreating line like the projected shadow or light always underlining the single-eyed perspective in photography. We recognise the places and at the same central viewpoint in Di Liborio’s images, but his greys are richer, they press much closer to the signs and identified forms, apparently cataloguing them, but actually projecting them, in a way not dissimilar from the series by this author on tourist imagery (Turista per gioco, Tourist for fun, 1993, which in my opinion owes something to Ghirri ‘s Atlante) and on a journey within his own house (Via Parma 14, 1998). Of course, the Pop iconography of household objects is here perforce abandoned in favour of a much more dilated time reminiscent of Morandi, Klein, blooming dampness. It is as if by coming closer to the surfaces, to the outer shell of this place that is about to disappear, reading times slowed down, mellowed, and the eye of the camera became a caress.

PAOLO BARBARO

March 1999